Picture this: 1984. Somewhere in middle America where the roads stretch straight and empty for miles. Two vehicles racing side by side down sun-bleached asphalt—a car packed with four girls, windows down, and a pickup truck.

The preacher’s daughter is in that car. Then her boyfriend pulls up alongside, grinning, challenging, and she makes a choice that defines everything about who she is.

She climbs out. Whilst both vehicles are moving, whilst a semi-truck is barrelling straight towards them in the opposite lane. During the transfer between moving vehicles, she deliberately stands with one foot planted on each car, legs split wide in a perfect gymnastic pose, blonde hair caught in the wind, suspended between two worlds whilst metal and machinery hurtle towards collision.

The girls are screaming. The boyfriend’s terrified. She’s exhilarated.

The semi’s getting closer. Seconds left, maybe less.

She waits. Not frozen—waiting. Choosing the exact moment. Then she jumps into the pickup and they swerve with inches to spare.

That’s Lori Singer as Ariel Moore in Footloose. The scene that shows you exactly who this character is without a single word of dialogue.

Within a decade, Hollywood will have moved on.

But here’s what you didn’t know: Before Hollywood, before Footloose made her famous, she was already performing—at thirteen, as a solo cellist with the Oregon Symphony. At fourteen, she became Juilliard’s youngest student. At twenty-six, she was choosing between Carnegie Hall and Paramount Pictures. She chose both. Then Hollywood made her choose again. And when she chose wrong—chose interesting over profitable, art over commerce—they made her pay for it.

What happens when a woman who could have been anything decides that neither version of Hollywood’s success is worth what it costs?

The House Where Excellence Wasn’t Optional

Lori Jacqueline Singer didn’t just grow up around music. She grew up inside it.

Her father, Jacques Singer, was a Polish-born conductor who’d studied under Leopold Stokowski and led orchestras from Dallas to Portland. Her mother, Leslie Wright, was a concert pianist. Leonard Bernstein and Aaron Copland came to dinner. The living room doubled as a rehearsal space for world-class musicians. This wasn’t a childhood—it was an eighteen-year audition for excellence.

Four children, all performers. Marc Singer became an actor—the Beastmaster, Mike Donovan in V. Gregory, Lori’s fraternal twin, became a violinist and conductor. Even Claude became a brand strategist and historian—still a storyteller, just not on stage.

The family moved constantly for Jacques’s work. Corpus Christi, Texas, where Lori was born on 6th November 1957. Portland, Oregon. New York City. Lori practised cello four to five hours every day. At thirteen, she made her solo debut with the Oregon Symphony—not a student showcase, a full orchestral performance.

Her godfather was Yehudi Menuhin, one of the greatest violinists of the 20th century. Her uncle Sidney Foster was a concert pianist who’d won the Leventritt Prize.

This level of pedigree doesn’t open doors. It demolishes walls.

The path was clear: Lori would be a virtuoso. Like her parents. Like her uncle. Like everyone in the family who’d ever picked up an instrument.

Juilliard at Fourteen, Carnegie Hall Waiting

At fourteen, Lori was admitted to Juilliard to study under Leonard Rose, whose students included Yo-Yo Ma and Lynn Harrell. She became the school’s youngest graduate—an achievement that sounds impossible until you remember that in the Singer household, prodigy was expected, not celebrated.

After Juilliard came performances with the Western Washington Symphony. In 1980, she won the Bergen Philharmonic Competition. Carnegie Hall bookings followed. The path was clear: fifty years of concert halls, recordings, master classes.

But Lori was watching her brother Marc.

He’d gone into acting. Hollywood, not orchestras. The work looked different—less about technical perfection, more about emotional truth. “In a world where such terrible things are happening,” she’d say years later, “it’s just so fantastic to become someone else.”

So whilst still performing concerts, she signed with Elite Modelling Agency. Tall, blonde, blue-eyed, with bone structure that photographed like sculpture. She juggled modelling gigs with symphony performances. The contradiction didn’t trouble her.

Why choose one thing when you could master several?

Fame: The Role Custom-Built for a Cellist Who Could Dance

In 1982, Lori auditioned for Fame, the NBC television series that continued the story of Alan Parker’s gritty 1980 film about performing arts students at New York’s High School of Performing Arts. The show didn’t soften the film’s edge—it was still raw, still honest about the brutality of artistic training, still willing to show young people destroying themselves in pursuit of excellence.

The role of Julie Miller was written specifically for Lori Singer’s unique combination of skills: a dancer who also played cello, navigating the savage world of professional arts training whilst trying to figure out who she actually was beneath all the technique and discipline. She was cast for the first two seasons, appearing from 1982 to 1983 as one of the show’s central characters.

In 1983, the entire Fame cast performed at Royal Albert Hall in London—7,000 seats, every single one filled with fans who’d connected with the show’s unflinching portrayal of young artists. The concert was recorded and released as a live album. Singer won the ShoWest Newcomer award for her work in the television film Born Beautiful.

Casting directors were circling. Film offers were arriving. Hollywood was interested in the classically trained musician who could act, who could move, who photographed like a dream and brought genuine skill to every frame.

Hollywood noticed. Hollywood always notices beautiful women who can act.

The question—the question it always comes down to with beautiful women in Hollywood—was whether they’d let her be anything more than beautiful.

Footloose: High Speed Splits, Real Violence, and a Star-Making Performance

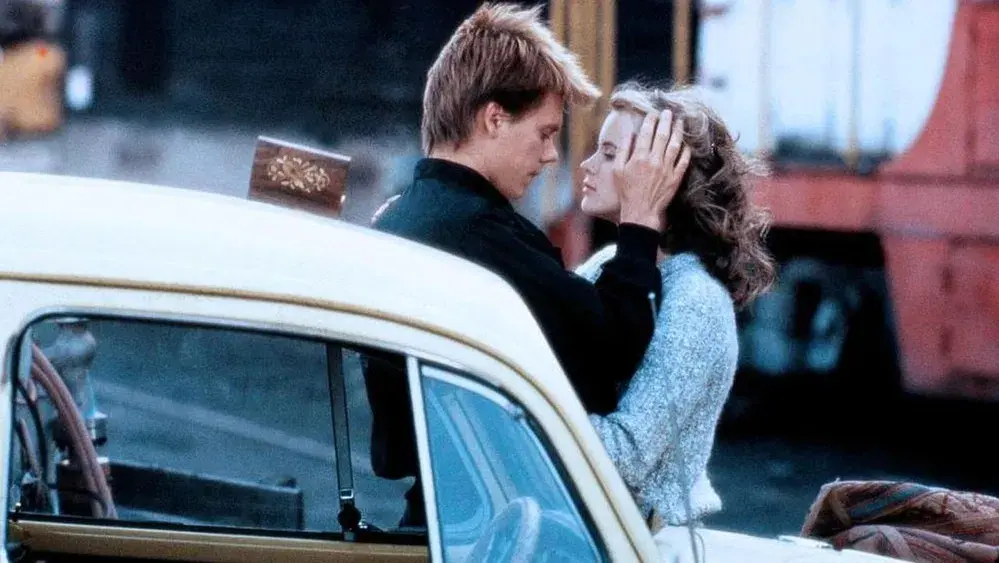

Herbert Ross’s Footloose (1984) shouldn’t have been anything special on paper. Teen dance movie. City kid (Kevin Bacon) moves to repressive small town. Dancing is banned by fire-and-brimstone preacher (John Lithgow). Standard 80s formula about rebellion and self-expression and finding your voice.

Footloose (1984) Gallery: TMDB

Except Lori Singer didn’t play Ariel Moore, the preacher’s tortured daughter, like a standard 80s formula character.

She played her like a bomb that’s been ticking for eighteen years, pressure building with nowhere to release, just waiting for someone to show up and light the fuse.

This is who she is: someone who’d rather risk death than back down, someone who’s been so controlled by her father’s rules that the only way to feel alive is to court destruction.

The film grossed over £80 million domestically. Massive numbers for 1984. Singer won the ShoWest Breakthrough Performer of the Year award. Pauline Kael, the critic whose reviews could end careers with a single devastating paragraph, wrote in The New Yorker:

“She has a startling, zingy radiance; she obliterates the other people on the screen.”

Years later, in 2024 interviews for the film’s 40th anniversary, Singer would recall that the chemistry with Kevin Bacon was “natural… electric.” The kind of on-screen connection that can’t be manufactured in rehearsal, can’t be taught in acting classes, can’t be faked for the camera.

She was twenty-six years old. She’d been famous in classical music circles for over a decade. Now she was famous everywhere, recognisable to millions who’d never heard of Leonard Rose or the Bergen Philharmonic Competition.

Hollywood offered her the world, as long as she kept playing the same character in different costumes.

The Follow-Ups: When Interesting Doesn’t Pay the Bills

After Footloose, Lori Singer could have had any role she wanted—as long as it was another version of Ariel Moore. The beautiful blonde in crisis. The troubled daughter. The love interest who looks ethereal whilst men around her have actual character arcs.

She chose differently. She chose scripts that interested her, directors who challenged her, characters with complexity that went beyond “girl who needs saving” or “girl who inspires the hero.”

The Falcon and the Snowman (1985)

John Schlesinger’s espionage thriller starring Timothy Hutton and Sean Penn, based on the true story of two California kids who sold American secrets to the Soviets. Critically acclaimed, celebrated at festivals, modest box office returns. Singer played Hutton’s girlfriend with quiet desperation, a woman watching her boyfriend destroy his life and unable to stop it.

The Man with One Red Shoe (1985)

A Tom Hanks comedy that was supposed to be a commercial breakthrough. It wasn’t. The film flopped spectacularly, dismissed by critics and ignored by audiences, taking Singer’s commercial momentum with it.

Trouble in Mind (1985)

Alan Rudolph’s neo-noir set in a dystopian Pacific Northwest that felt like Blade Runner filtered through Raymond Chandler. Singer earned an Independent Spirit Award nomination for playing Georgia, a woman caught between violence and survival in a world where both seem inevitable. Film critics loved it. The general public stayed home.

Summer Heat (1987)

Where she played a dissatisfied farm wife having an affair during Depression-era America. Critics praised her performance as nuanced and brave. The box office barely registered the film’s existence.

Warlock (1989)

A horror film about a witch hunter chasing a time-travelling warlock through modern Los Angeles. It became a cult classic, beloved by horror fans, quoted and referenced for decades. It didn’t become a hit during its theatrical run.

None of these films matched Footloose‘s commercial success. None of them were supposed to. Singer wasn’t interested in being Ariel Moore for the next forty years—she wanted roles that mattered, scripts that challenged her assumptions about performance, characters with internal lives that extended beyond their function in male protagonists’ journeys.

Hollywood doesn’t reward interesting choices. It rewards profitable ones. And Hollywood really doesn’t forgive women who choose quality over commercial appeal.

By the early 1990s, the scripts were arriving less frequently. The roles were getting smaller, the budgets tighter, the directors less prestigious. The phone didn’t ring as often as it used to.

The machinery was already grinding her down, the same machinery that’s ground down every woman who ever thought talent and dedication might be enough.

The Marriage That Exploded in Courtrooms

In 1980, at the height of her Juilliard fame and just before Fame made her a television star, Lori married Richard David Emery, a prominent civil rights lawyer and founding partner of Emery, Celli, Brinckerhoff & Abady LLP. Emery wasn’t just any attorney—he was New York legal royalty, the kind of lawyer who argued cases before the Supreme Court and won, who served on Governor Mario Cuomo’s State Commission on Government Integrity, who represented wrongly convicted prisoners in high-profile exonerations that made national news.

They had a son together, Jacques Rio Emery, born in March 1991. From the outside, viewed through the lens of society pages and industry gossip, it looked stable—successful actress married to crusading lawyer, beautiful child, Manhattan life, the whole package.

From the inside, the marriage was already fracturing along fault lines that would eventually tear everything apart.

The Legal Battle: 1996-2000

Singer largely disappeared from public view whilst the legal battles consumed her life.

Short Cuts: Altman’s Masterpiece and Her Finest Performance

Before the disappearance, before VR.5 was cancelled and the divorce consumed everything, Singer had delivered what many critics still consider her finest screen performance.

Robert Altman’s Short Cuts (1993) wove together Raymond Carver short stories into a sprawling ensemble piece about modern American dysfunction—infidelity, rage, grief, disconnection, all set in Los Angeles during a Mediterranean fruit fly invasion that serves as both literal event and metaphorical contamination. The cast included Andie MacDowell, Julianne Moore, Tim Robbins, Robert Downey Jr., Frances McDormand, Lily Tomlin, Matthew Modine, and a dozen other actors at the top of their craft.

Singer played Zoe Trainer, a cellist performing in “The Trout Quintet.” Her performance was devastating in its quietness, in what it refused to give the audience. She didn’t have long monologues or dramatic breakdown scenes. She had silence, deadened eyes, and a cello that she played with perfect technical precision whilst something fundamental inside her was breaking.

She played her own cello on the film’s soundtrack. Of course she did. By this point, she’d been playing for over twenty years, maintaining her technique even as acting consumed more of her time and attention.

The film won the Golden Globe for Best Ensemble Cast—an award that recognised what Altman had achieved in getting this many skilled actors to subordinate ego to collective storytelling. It was a reminder, to Singer and to Hollywood and to anyone paying attention, that she’d always been more than the industry allowed her to be.

Hollywood wasn’t interested in being reminded. Hollywood was already moving on to younger actresses who hadn’t yet learned to say no.

VR.5: The Cult Series That Became Her Last Regular Role

In 1995, whilst still navigating the aftermath of her disintegrating marriage, Singer headlined VR.5, a Fox science fiction series about a woman who discovers she can enter a dangerous level of virtual reality where consciousness itself becomes malleable. The show tackled conspiracy theories before they became internet currency, government surveillance before Snowden, identity questions before The Matrix made them mainstream.

Critics appreciated it. A cult following developed. Fox aired ten episodes and cancelled it.

It was Singer’s last regular television role. She was thirty-eight years old.

She didn’t announce retirement. She just stopped auditioning. Stopped chasing pilot season. Stopped playing the game that requires constant visibility and willingness to be reduced to a headshot and a type.

She returned to music—chamber concerts, private events, venues that didn’t require her face on a poster.

For the next fifteen years, if you searched for Lori Singer, you’d find almost nothing. A guest spot here. A documentary credit there. References to Footloose in 80s retrospectives.

Mostly silence.

The woman who’d obliterated everyone else on screen was playing cello for audiences of fifty people in concert halls nobody outside classical music circles had heard of.

That wasn’t her choice. That was what Hollywood left her.

Discover where they are now! Browse our full archive of iconic cast retrospectives.

The Documentary Years: Emmys Instead of Red Carpets

In 2008, Lori Singer performed at Carnegie Hall—the venue she’d been headed towards since childhood, the stage that represented everything her Juilliard training had prepared her for. She premiered a hymn written by Karl Jenkins in memory of Martin Luther King Jr. The performance received respectful reviews. Classical music publications noted her continued technical skill.

In 2011, she reappeared on television with a guest role on Law & Order: SVU, playing a murder victim’s sister in an episode that dealt with domestic violence and institutional failure. It was a small role, maybe ten minutes of screen time. She was excellent in it.

Entertainment blogs noticed. Questions started appearing: “Where has Lori Singer been?” “What happened to the Footloose star?” “Remember her?”

The answer was simple: she’d been working. Just not where Hollywood was looking.

Singer had discovered documentary filmmaking, and it turned out she was exceptional at it—not just as a performer, but as a producer and shaper of investigative narratives.

In 2012, she executive produced Mea Maxima Culpa: Silence in the House of God, Alex Gibney’s documentary investigating systematic sexual abuse by a priest at a school for the deaf and the Catholic Church’s decades-long cover-up. Four Primetime Emmys. A Peabody. Oscar shortlist. Singer had substantially contributed to the film’s concept and treatment, not just her name on the credits.

In 2016, she executive produced and narrated God Knows Where I Am, about a woman with mental illness who died alone in an abandoned farmhouse after being released from psychiatric care with nowhere to go. Singer’s voiceover—reading the dead woman’s diary entries—was praised by Variety as “vivid” and emotionally precise. Toronto Hot Docs winner. Emmy Award. Twenty-plus festival prizes.

This was the work Singer cared about. Not red carpets. Not celebrity. Truth-telling. Investigation. Exposing systems that failed the vulnerable.

The documentary work won more awards than her acting career ever had.

Hollywood still wasn’t watching. Hollywood had moved on decades ago.

Read Next

From the Vault